The blurring cascade of hyperspace speedily resolved itself into streaking starlines and finally the black of space. Kiara Fen shut down the hyperdrive, and killed all unnecessary power. Slowly, she brought the sublight drive up to power, matching the acceleration of the freighter she was tucked underneath. How To Make Sure Little Snitch Blocks Itself Auto Tune Implants Throat Antares Auto-tune Evo Rtas Free Download Traktor 2 Pro Native Instrumentsapp Sansamp Free Vst Download Traktor S4 Mk2 With Kaossilator Pro And Kp3 Bass Rider Vst Download Free Mac Bartender Fallout 4 Using 3utools To Put Videos On Ipad.

where every moment is an adventure and fascination is your constant state of being.'

Ken Boyd

As we edged towards Christmas 1944, I wrote:

“Everything we do, think of, or talk about, concerns the show up ahead. The din and totalness of battle that was all around me here just a few months ago, is now deader than a cemetery. In those days I felt the whole War was being fought right here and that perhaps the people back home didn’t understand or appreciate what the soldiers were going through. Now we find ourselves helping others to prepare to join the action further on, and hoping we can get there on our next assignment….we’ve learned first hand how important it is to make sure shoes, clothing, cigarettes and a variety of canned meat reach the front lines.

This Island will always be remembered by the Army Infantrymen as the place that was once swimming in Spam….Dust is everywhere here now. Sometimes you have to stop when driving a jeep or truck, just to see the road….Please don’t feel that your descriptions of home will make us homesick. We think about home whether we get mail or not. I always want to read about what you are doing….I find myself dreaming and restless again, just as I did in New York Harbor. Crossing the Country and boarding our troopship was a dream come true. I had never crossed a lake before, let alone an ocean. Now It’s time to move on again. I wouldn’t be opposed to orders returning me to the States, either. It’s time to leave our present location!

“The Aussies have moved in behind us all the way up the Coast of New Guinea and we can’t wait for them to take over control on Biak as well….Our evening coffee discussions have turned to religion lately. There is agreement about a religious revival, and this is particularly true with the Enlisted Men. None of the Officers admit they are becoming more spiritual, but we all seem to agree we’re learning to be tolerant of the other’s guy’s beliefs. At least I’m learning to keep my mouth shut, especially when talking to a “Limey!”

. . . As we prepared for Christmas 1944, I suffered a personal loss when a great priest, Father John Halloran and the rest of the 41st Division were loaded on LSTs for the run to the action in the Philippines. In his final Mass in the “Tented” Chapel, he said he had hoped he’d still be here with his flock for Christmas. He reminded them of the plan to establish a Choir. He recalled 14 other chapels the Division had built all over New Guinea, and how they spent a month in one, two weeks in another, and six hours in a recent one before moving out. Everyone knew something was up when he passed out cards to the troops for mailing home. The text said: “I’ll be receiving Holy Communion for you on Christmas”.

Next day, many of my friends and MacArthur’s favorite Infantry Division, packed up their war gear once again for new foxholes, canned rations, and more gunfire and dead soldiers. Their departure was guarded and friends were unable to say goodbye, I felt sure we’d meet again. Halloran was without a doubt, one of the finest men I’d ever met. His main reason for being overseas was a total dedication to his troops. They were his congregation.

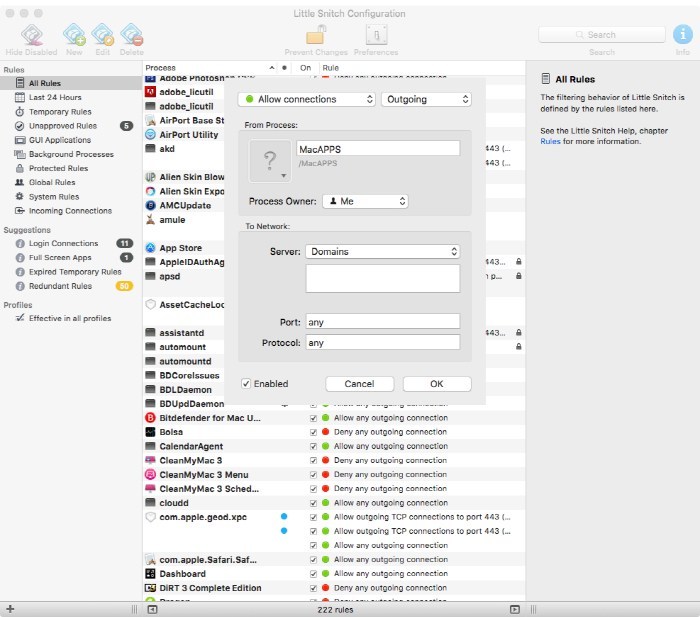

Make Sure Little Snitch Blocks Itself Go

One way to fill up censored letters home was to pick a subject about the past and reminisce about it with the keys of a typewriter. It also helped to keep me sane. Since we were approaching Christmas, an attempt was made to recapture and review thoughts that my family would remember from the past. An example:

“I remember the turmoil before the Christmas tree actually went up. Mom always said she had done her part when she bought the tree down at Jimmy Dykes’s place. Then Daddy would always say the tree was crooked, covering up the fact that he was in pain from having hit his finger with the hammer. And Shirley would find something to cry about, while Margaret would have to go out to deliver a gift for some friend. And Larry always seemed to be elsewhere, perhaps at friend Jimmy O’Hora’s house, or maybe at work in Jimmy Sample’s drugstore. My place in those Christmas Eve pictures is hazy. I only remember I was in the way”. (We had no car. I wonder now how we ever got the tree home from three blocks away).

In the 1944 letters I remembered something long since forgotten. Kids would always be ringing our doorbell on Ward Street at Christmas. Like the modern “Trick or Treaters” they would ask: “Can we come in and see Yer tree”. It obviously called for a handout of gifts of candy. I betrayed a lonesome mood when I closed one letter with: “No matter who stands out at this year’s Holiday activities, my best wishes to everyone for a very Merry Christmas; my thoughts will be with you all. I just wish I could ring your doorbell and ask to “see Yer tree!”

[there is more to come]

My friend in Irvine has extreme macular degeneration in one eye. The other eye, he says, still has 'immaculate perception.' I still have not figured out #10; 'Flies like an arrow???' A garbage truck has four wheels and flies. Where does time come in? Many thanks for keeping us posted. I love hearing from all the great minds of our Association. Merry Christmas to all. Bob Green (#3) [Editor's note: Bob's first line above is well received by me. I lost central vision in my left eye over three years ago but I have good peripheral vision in both eyes. I lost binocular vision and, accordingly, some depth perception. Reading is more difficult but I still enjoy it. 'Time flies like an arrow' is discussed below. That first word, 'time,' is important.] |

Breads: There is a vast variety of breads in the world. Every country, every section of a country, every culture, every rural and every urban area conjures up its own extensive selection of breads. In the two years [1961 to 1963] we spent in Jordan, every morning street vendors, mobilized at the crack of dawn, out on the hilly residential streets of Amman, with large flat boards balanced on their heads, held with one hand, loaded with rings of sesame kyak, loudly hawking their wares: 'Kya-a-k, kyak' - one long, one short shout, as inside, curled up in our warm beds, we stir comfortably. It was a quaintly peasant-like, friendly feeling that passed through your body on being awakened by these early rising bread makers and the fragrance of their freshly made bread.

In Jordan: there is also 'hubbus taboon', which, in smaller villages, is dough cooked on hot stones in an outdoor open fireplace, using unbleached burghol wheat. As a consequence of the shape of the hot stones, the bread comes forth full of small stone-sized hollows. Once, in the ancient town of Jericho, searching for an acceptable place to eat with our four children, we found ourselves on a small second story terrace of a restaurant, wondering what to order that would- in taste and health- suit us all. A very solicitous lady suggested the chicken on taboon. We weren't too sure, but chicken on bread seemed familiar and safe. She insisted that everyone liked it, including young and old tourists.

It came served over a large round loaf of this hubbus taboon, beladen with cooked onions and gravy poured over all. We loved the aroma of it and the taste was surprisingly good, too, though Tim, Rich, Mary and Chris each moved most of the onions to one side, then proceeded to eat all the rest with great satisfaction. Meanwhile, during the meal, small lizards could be watched scooting across the walls and the ceiling- harmless and largely ignored by the patrons. We were told that they kept off the insects! With grins, raised eyebrows and hunching of shoulders we accepted the justification for these unusual dinner companions.

In Bedouin desert country, beneath the huge black tents they live in, no matter the weather, a bread called Esshrak is made, being a thin dough (like pizza preparation). The fire for it could be in a hole in the ground, with a wire mesh over the top of the hole to accommodate the flattened dough. While it's cooking, chickens would be pecking at the dough and a bedouin lady would occasionally throw a handful of sand at them, sending them off fluttering, clucking surprise at the treatment. No matter what, the bread always seems to be excellent, and the cooking of it over a hot open fire has made it safe eating for everyone.

On one of my sojourns in Egypt, Cecilia, Mary and Chris spent a month living in Maadi, a residential suburb of Cairo- largely for foreign Embassy personnel while I worked with a consortium of companies on the economics of a Master Plan for the new Sadat City, to be located between Cairo and Alexandria. For bread, we would shop at this small hut-like bakery, lighted only by the flames from the ovens. It was dark and mysterious- like approaching a service counter in Hades- flames piercing the dark, and the sweet, pungent fumes taking over. You had to bring your own bag to carry the bread, as no bags would be provided. The scent of bread was so strong you could almost taste it as you approached from a distance. The system seemed almost too primitive to yield such wonderful bread, yet we have not ingested better anywhere.

In France, the bread and all of the pastries are superb. France, of course, is famous for its pastry shops. Its croissants and all manner of biscuits are unmatched anywhere. The long, crusty French bread loaves are also great.

There is the comedy about French biscuits related in a short TV film of how this French bakery prepared these superb rolls in a tiny shop, hardly bigger than the large flaming oven itself. While removing the rolls from the oven, some fell on the bakery floor around the oven. They were hurriedly retrieved and put in a large basket and hustled out to the delivery wagon. When the baskets of rolls on the wagon were full, the driver climbed up to the wagon seat, touched the horse lightly with his whip and off he went to deliver his baskets of rolls. However, when taking the next corner, a couple of baskets fell off the wagon, tumbling the rolls all over the road. The driver jumped down and feverishly picked them up and returned them to the baskets. Again, he flicked the whip toward the horse and off toward the Ritz Hotel he went with his first delivery.

At the hotel, these rolls, which had twice fallen to the pavements- at the bakery and on the sharp street turn- were hurried into the steel- shiny chef's kitchen of the Ritz, where they were soon placed on a garlanded silver tray and taken by an immaculate white-coated waiter to the penthouse suite, where they were served to an aristocrat from England and his wife for breakfast; no one on the consumption end ever being the wiser as to the humble origins of those rolls, nor of the ignominious- not to say unsanitary- exposure these delicacies had experienced on the way to that elegant penthouse suite.

Paragraphs could be written about the wonderful Indian breads one gets at Indian restaurants, as well as, naturally, in India- fried, fluffy Puri, big, thick Nan, Roti, roasted on fiery charcoal, and the fried, thick-layered Paratha. The Italian bread foccacia, taken with any spread, or dipped in olive oil spiced up with salt, mixed ground peppercorns and grated cheese, is superb! You can travel around the world and exist safely- as I have good cause to know - on tea (or beer) and the local breads made, whether in Europe, Asia, Africa, the Middle East, East or West Indian Islands, wherever. The breads of the world are truly outstanding and someone could and should write a good- and fascinating- book about them.

A band was hired, and the first floor made an ideal dance floor. The event was well attended by women from the nearby neighborhoods, who were invited to the party. Plenty of sandwiches and beer were available to all, and everyone agreed it was a fine party.

'With the pre-commissioning period coming to an end, the crew was quartered in the Receiving Station on Terminal Island until the ship was ready. A watch was set up on the 'quarter deck'. But the outstanding impression and memory which lingered was the stench from nearby fish canneries.

On 11 October the Beach Party arrived, making only the absent Boat Group necessary to complete the crew. Unfortunately the Boat Group did not arrive until after the commissioning.

On 15 October the crew had a preview of how the Bladen would behave, as she sailed out on a trial run with key officers and enlisted men who joined experts from Consolidated. The results of this trial run would determine whether the Navy would determine the ship was satisfactory and accept it. She behaved as was hoped, and was accepted by the Navy.

On 16 October the ship was ignominiously towed from the Consolidated Yard to a dock several miles away at Terminal Island, arriving at 2100 hours. The crew ate an early dinner at the Receiving Station that day, picked up their gear, and were transported to the dock where the Bladen was moored. The crew went aboard, and were immediately put to work loading supplies. . . .

[next week: Christmas at sea.]

** ANOTHER DOZEN PUNS

(from Tom Lange)

** ED VEZEY

Ed Vezey was in town several days last week. Here we are on a high overlook near the northern end of this island. Ed is on your right. Behind us a rugged, inaccessible (?) coast extends ten miles to the southeast.

Stubby Pringle's Christmas

A short story by

Jack SchaeferHigh on the mountainside by the little line cabin in the crisp clean dusk of evening Stubby Pringle swings into saddle. He has shape of bear in the dimness, bundled thick against cold. Double socks crowd scarred boots. Leather chaps with hair out cover patched corduroy pants. Fleece-lined jacket with wear of winters on it bulges body and heavy gloves blunt fingers. Two gay red bandannas folded together fatten throat under chin. Battered hat is pulled down to sit on ears and in side pocket of jacket are rabbit-skin earmuffs he can put to use if he needs them.

Stubby Pringle swings up into saddle. He looks out and down over worlds of snow and ice and tree and rock. He spreads arms wide and they embrace whole ranges of hills. He stretches tall and hat brushes stars in sky. He is Stubby Pringle, cowhand of the Triple X, and this is his night to howl. He is Stubby Pringle, son of the wild jackass, and he is heading for the Christmas dance at the schoolhouse in the valley.

Stubby Pringle swings up and his horse stands like rock. This is the pride of his string, flop-eared ewe-necked cat-hipped strawberry roan that looks like it should have died weeks ago but has iron rods for bones and nitroglycerin for blood and can go from here to doomsday with nothing more than mouthfuls of snow for water and tufts of winter-cured bunch-grass snatched between drifts for food. It stands like rock. It knows the folly of trying to unseat Stubby. It wastes no energy in futile explosions. It knows that twenty-seven miles of hard winter going are foreordained for this evening and twenty-seven more of harder uphill return by morning. It has done this before. It is saving the dynamite under its hide for the destiny of a true cowpony which is to take its rider where he wants to go – and bring him back again.

Stubby Pringle sits in his saddle and he grins into cold and distance and future full of festivity. Join me in a look at what can be seen of him despite the bundling and frosty breath vapor that soon will hang icicles on his nose. Those are careless haphazard scrambled features under the low hatbrim, about as handsome as a blue boar’s snout. Not much fuzz yet on his chin. Why, shucks, is he just a boy? Don’t make that mistake, though his twentieth birthday is still six weeks away. Don’t make the mistake Hutch Handley made last summer when he thought this was young unseasoned stuff and took to ragging Stubby and wound up with ears pinned back and upper lip split and nose mashed flat and the whole of him dumped in a rainbarrel. Stubby has been taking care of himself since he was orphaned at thirteen. Stubby has been doing man’s work since he was fifteen. Do you think Hardrock Harper of the Triple X would have anything but an all-around hard-proved hand up here at his farthest winter line camp siding Old Jake Hanlon, toughest hard-bitten old cowman ever to ride range?

Stubby Pringle slips gloved hand under rump to wipe frost off the saddle. No sense letting it melt into patches of corduroy pants. He slaps rightside saddlebag. It contains a burlap bag wrapped around a two-pound box of candy, of fancy chocolates with variegated interiors he acquired two months ago and has kept hidden from Old Jake. He slaps leftside saddlebag. It holds a burlap bag wrapped around a paper parcel that contains a close-folded piece of dress goods and a roll of pink ribbon. Interesting items, yes. They are ammunition for the campaign he has in mind to soften the affections of whichever female of the right vintage among those at the schoolhouse appeals to him most and seems most susceptible.

Stubby Pringle settles himself firmly into the saddle. He is just another of far-scattered poorly-paid patched-clothes cowhands that inhabit these parts and likely marks and smells of his calling have not all been scrubbed away. He knows that. But this is his night to howl. He is Stubby Pringle, true-begotten son of the wildest jackass, and he has been riding line through hell and highwater and winter storms for two months without a break and he has done his share of the work and more than his share because Old Jake is getting along and slowing some and this is his night to stomp floorboards till schoolhouse shakes and kick heels up to lanterns above and whirl a willing female till she is dizzy enough to see past patched clothes to the man inside them. He wriggles toes deep into stirrups and settles himself firmly in the saddle.

“I could of et them choc’lates,” says Old Jake from the cabin doorway. “they wasn’t hid good,” he says. “No good at all.”

“An’ he beat like a drum,” says Stubby. “An’ wrung out like a dirty dishrag.”

“By who?” says Old Jake. “By a young un like you? Why, I’d of tied you in knots afore you knew what’s what iffen you tried it. You’re a dang-blatted young fool,” he says. “A ding-busted dang-blatted fool. Riding out a night like this iffen it is Chris’mas eve. A dong-bonging ding-busted dang-blatted fool,” he says. “But iffen I was your age agin, I reckon I’d be doing it too.” He cackles like an old rooster. “Squeeze one of ‘em for me,” he says and he steps back inside and he closes the door.

Stubby Pringle is alone out there in the darkening dusk, alone with flop-eared ewe-necked cat-hipped roan that can go to the last trumpet call under him and with cold of wicked winter wind around him and with twenty-seven miles of snow-dumped distance ahead of him. “Wahoo!” he yells. “Skip to my Loo!” he shouts. “Do-si-do and round about!”

He lifts reins and the roan sighs and lifts feet. At easy warming-up amble they drop over the edge of benchland where the cabin snugs into tall pines and on down the great bleak expanse of mountainside.

Stubby Pringle, spurs a jingle, jobs upslope through crusted snow. The roan, warmed through, moves strong and steady under him. Line cabin and line work are far forgotten things back and back and up and up the mighty mass of mountain. He is Stubby Pringle, rooting, tooting hard-working hard-playing cowhand of the Triple X, heading for the Christmas dance at the schoolhouse in the valley.

He tops out on one of the lower ridges. He pulls rein to give the roan a breather. He brushes an icicle off his nose. He leans forward and reaches to brush several more off sidebars of old bit in the bridge. He straightens tall. Far ahead, over top of last and lowest ridge, on into the valley, he can see tiny specks of glowing allure that are schoolhouse windows. Light and gaiety and good liquor and fluttering skirts are there. “Wahoo!” he yells. “Gals an’ women an’ grandmothers!” he shouts. “Raise your skirts and start askipping! I’m acoming!”

He slaps spurs to roan. It leaps like mountain lion, out and down, full into hard gallop downslope, rushing, reckless of crusted drifts and ice-coated bush-branches slapping at them. He is Stubby Pringle, born with spurs on, nursed on tarantula juice, weaned on rawhide, at home in the saddle of a hurricane in shape of horse that can race to outer edge of eternity and back, heading now for highjinks two months overdue. He is ten feet tall and the horse is gigantic, with wings, iron-boned and dynamite-fueled, soaring in forty-foot leaps down the flank of the whitened wonder of a winter world.

They slow at the bottom. They stop. They look up the rise of the last low ridge ahead. The roan paws frozen ground and snorts twin plumes of frosty vapor. Stubby reaches around to pull down fleece-lined jacket that has worked a bit up back. He pats rightside saddlebag. He pats leftside saddlebag. He lifts reins to soar up and over last low ridge.

Make Sure Little Snitch Blocks Itself Get

Hold it, Stubby. What is that? Off to the right.

He listens. He has ears that can catch snitch of mouse chewing on chunk of bacon rind beyond the log wall by his bunk. He hears. Sound of ax striking wood.

What kind of dong-bonging ding-busted dang-blatted fool would be chopping wood on a night like this and on Christmas Eve and with a dance underway at the schoolhouse in the valley? What kind of chopping is this anyway? Uneven in rhythm, feeble in stroke. Trust Stubby Pringle, who has chopped wood enough for cookstove and fireplace to fill a long freight train, to know how an ax should be handled.

There. That does it. That whopping sound can only mean that the blade has hit at an angle and bounced away without biting. Some dong-bonged ding-busted dang-blatted fool is going to be cutting off some of his own toes.

He pulls the roan around to the right. He is Stubby Pringle, born to tune of bawling bulls and blatting calves, branded at birth, cowman raised and cowman to the marrow, and no true cowman rides on without stopping to check anything strange on range. Roan chomps on bit, annoyed at interruption. It remembers who is in saddle. It sighs and obeys. They move quietly in dark of night past boles of trees jet black against dim greyness of crusted snow on ground. Light shows faintly ahead. Lantern light through a small oiled-paper window.

Yes. Of course. Just where it has been for eight months now. The Henderson place. Man and woman and small girl and waist-high boy. Homesteaders. Not even fools, homesteaders. Worse than that. Out of their minds altogether. All of them. Out here anyway. Betting the government they can stave off starving for five years in exchange for one hundred sixty acres of land. Land that just might be able to support seven jack-rabbits and two coyotes and nine rattlesnakes and maybe all of four thin steers to a whole section. In a good year. Homesteaders. Always out of almost everything, money and food and tools and smiles and joy of living. Everything. Except maybe hope and stubborn endurance.

Stubby Pringle nudges the reluctant roan along. In patch-light from the window by a tangled pile of dead tree branches he sees a woman. Her face is grey and pinched and tired. An old stocking-cap is pulled down on her head. Ragged man’s jacket bumps over long Woolsey dress and clogs arms as she tries to swing an ax into a good-sized branch on the ground.

Whopping sound and ax bounces and barely misses an ankle.

“Quit that!” says Stubby, sharp. He swings the roan in close. He looks down at her. She drops ax and backs away, frightened. She is ready to bolt into two-room bark-slab shack. She looks up. She sees the haphazard scrambled features under low hatbrim are crinkled in what could be a grin. She relaxes some, hand on door latch.

“Ma’am,” says Stubby. “You trying to cripple yourself?” She just stares at him. “Man’s work,” he says. “Where’s your man?”

“Inside,” she says, then, quick, “He’s sick.”

“Bad?” says Stubby.

“Was,” she says. “Doctor that was here this morning thinks he’ll be all right now. Only he’s almighty weak. All wobbly. Sleeps most of the time.”

“Sleeps,” says Stubby, indignant. “When there’s wood to be chopped.”

“He’s been almighty tired,” she says, quick, defensive. “Even afore he was took sick. Wore out.” She is rubbing cold hands together, trying to warm them. “He tried,” she says, proud. “Only a while ago. Couldn’t even get his pants on. Just feel flat on the floor.”

Stubby looks down at her. “An’ you ain’t tired?” he says.

“I ain’t got time to be tired,” she says. “Not with all I got to do.”

Stubby Pringle looks off past dark boles of trees at last row ridge top that hides valley and schoolhouse. “I reckon I could spare a bit of time,” he says. “Likely they ain’t much more’n started yet,” he says. He looks again at the woman. He sees grey pinched face. He sees cold-shivering under bumpy jacket. “Ma’am,” he says. “Get on in there an’ warm your gizzard some. I’ll just chop you a bit of wood.”

Roan stands with dropping reins, ground-tied, disgusted. It shakes head to send icicles tinkling from bit and bridle. Stopped in midst of epic run, wind-eating, mile-gobbling, iron-boned and dynamite-fueled, and for what? For silly chore of chopping.

Fifteen feet away Stubby Pringle chops wood. Moon is rising over last low ridgetop and its light, filtered through trees, shines on leaping blade. He is Stubby Pringle, moonstruck maverick of the Triple X, born with ax in hands, with strength of stroke in muscles, weaned on whetstone, fed on cordwood, raised to fell whole forests. He is ten feet tall and ax is enormous in moonlight and chips fly like stormflakes of snow and blade slices through branches thick as his arm, through logs thick as his thigh.

He leans ax against a stump and he spreads arms wide and he scoops up whole cords at a time and strides to door and kicks it open . . .

Both corners of front room by fireplace are piled full now, floor to ceiling, good wood, stout wood, seasoned wood, wood enough for a whole wicked winter week. Chore done and done right, Stubby looks around him. Fire is burning bright and well-fed, working on warmth. Man lies on big old bed along opposite wall, blanket over, eyes closed, face grey-pale, snoring long and slow. Woman fusses with something at old woodstove. Stubby steps to doorway to backroom. He pulls aside hanging cloth. Faint in dimness inside he sees two low bunks and in one, under an old quilt, a curly-headed small girl and in the other, under other old quilt, a boy who would be waist-high awake and standing. He sees them still and quiet, sleeping sound. “Cute little devils,” he says.

He turns back and the woman is coming toward him, cup of coffee in hand, strong and hot and steaming. Coffee the kind to warm the throat and gizzard of choredoing, hard-chopping cowhand on a cold cold night. He takes the cup and raises it to his lips. Drains it in two gulps. “Thank you, ma’am,” he says. “That was right kindly of you.” He sets cup on table. “I got to be getting along,” he says. He starts toward outer door.

He stops, hand on door latch. Something is missing in two-room shack. Trust Stubby Pringle to know what. “Where’s your tree?” he says. “Kids got to have a Christmas tree.”

He sees the woman sink down on chair. He hears a sigh come from her. “I ain’t had time to cut one,” she says.

“I reckon not,” says Stubby. “Man’s job anyway,” he says. “I’ll get it for you. Won’t take a minute. Then I got to be going.”

He strides out. He scoops up ax and strides off, upslope some where small pines climb. He stretches tall and his legs lengthen and he towers huge among trees swinging with ten-foot steps. He is Stubby Pringle, born an expert on Christmas trees, nursed on pine needles, weaned on pine cones, raised with an eye for size and shape and symmetry. There. A beauty. Perfect. Grown for this and for nothing else. Ax blade slices keen and swift. Tree topples. He strides back with tree on shoulder. He rips leather whangs from his saddle and lashes two pieces of wood to tree bottom, crosswise, so tree can stand upright again.

Stubby Pringle strides into shack, carrying tree. He sets it up, center of front-room floor, and it stands straight, trim and straight, perky and proud and pointed. “There you are, ma’am,” he says. He moves toward outer door.

He stops in outer doorway. He hears the sigh behind him. “We got no things,” she says. “I was figuring to buy some but sickness took the money.”

Stubby Pringle looks off at last low ridgetop hiding valley and schoolhouse. “Reckon I still got a bit of time,” he says. “They’ll be whooping it mighty late.” He turns back, closing door. He sheds hat and gloves and bandannas and jacket. He moves about checking everything in the sparse front room. He asks for things and woman jumps to get those few of them she has. He tells her what to do and she does. He does plenty himself. With this and with that magic wonders arrive. He is Stubby Pringle, born to poverty and hard work, weaned on nothing, fed on less, raised to make do with least possible and make the most of that. Pinto beans strung on thread brighten tree in firelight and lantern light like strings of store-bought beads. Strips of one bandanna, cut with shears from sewing-box, bob in bows on branch-ends like gay red flowers. Snippets of fleece from jacket-lining sprinkled over tree glisten like fresh falls of snow. Miracles flow from strong blunt fingers through bits of old paper-bags and dabs of flour paste into link chains and twisted small streamers and two jaunty little hats and two smart little boats with sails.

“Got to finish it right,” says Stubby Pringle. From strong blunt fingers comes five-pointed star, tiple-thickness to make it stiff, twisted bit of old wire to hold it upright. He fastens this to topmost tip of topmost bough. He wraps lone bandanna left around throat and jams battered hat on head and shrugs into now-skimpy-lined jacket. “A right nice little tree,” he says. “All you got to do now is get out what you got for the kids and put it under. I really got to be going.” He starts toward outer door.

He stops in open doorway. He hears the sigh behind him. He knows without looking around the woman has slumped into old rocking chair. “We ain’t got anything for them,” she says. “Only now this tree Which I don’t don’t mean it isn’t a fine grand tree. It’s more’n we’d of had ‘cept for you.”

Stubby Pringle stands in open doorway looking out into cold clean moonlit night. Somehow he knows without turning head two tears are sliding down thin pinched cheeks. “You go on along,” she says. “They’re good young uns. They know how it is. They ain’t expecting a thing.”

Stubby Pringle stands in open doorway looking out at last ridgetop that hides valley and schoolhouse. “All the more reason,” he says soft to himself. “All the more reason something should be there when they wake.” He sighs too. “I’m a dong-bonging ding-busted dang-blatted fool,” he says. “But I reckon I still got a mite more time. Likely they’ll be sashaying around till it’s most morning.”

Stubby Pringle strides on out, leaving door open. He strides back, closing door with heel behind him. In one hand he has burlap bag wrapped around paper parcel. In other hand he has squarish chunk of good pine wood. He tosses bag-parcel into lap-folds of woman’s apron.

“Unwrap it,” he says. “There’s the makings for a right cute dress for the girl. Needle-and-threader like you can whip it up in no time. I’ll just whittle me out a little something for the boy.”

Moon is high in cold cold sky. Frosty clouds drift up there with it. Tiny flakes of snow flat through upper air. Down below by a two-room shack droops a disgusted cowpony roan, ground-tied, drooping like statue snow-crusted. It is accepting the inescapable destiny of its kind which is to wait for its rider, to conserve deep-bottomed dynamite energy, to be ready to race to the last margin of motion when waiting is done.

Inside the shack fire in fireplace cheerily gobbles wood, good wood, stout wood, seasoned wood, warming two-rooms well. Man lies on bed, turned on side, curled up some, snoring slow and steady. Woman sits in rocking chair, sewing. Her head nods slow and drowsy and her eyelids sag weary but her fingers fly, stitch-stitch-stitch. A dress has shaped under her hands, small and flounced and with little puff-sleeves, fine dress, fancy dress, dress for smiles and joy of living. She is sewing pink ribbon around collar and down front and into fluffy bow on back.

On a stool nearby sits Stubby Pringle, piece of good pine wood in one hand, knife in other hand, fine knife, splendid knife, all-around-accomplished knife, knife he always has with him, seven-bladed knife with four for cutting from little to big and corkscrew and can opener and screwdriver. Big cutting blade has done its work. Little cutting blade is in use now. He is Stubby Pringle, born with feel for knives in hand, weaned on emery wheel, fed on shavings, raised to whittle his way through the world. Tiny chips fly and shavings flutter. There in his hands, out of good pine wood, something is shaping. A horse. Yes. Flop-eared ewe-necked cat-hipped horse. Flop-eared head is high on ewe neck, stretched out, sniffing wind, snorting into distance. Cat-hips are hunched forward, caught in crouch for forward leap. It is a horse fit to carry a waist-high boy to uttermost edge of eternity and back.

Stubby Pringle carves swift and sure. Little cutting blade makes final little cutting snitches. Yes. Tiny moltings and markings make no mistaking. It is a strawberry roan. He closes knife and puts it in pocket. He looks up. Dress is finished in woman’s lap. She sits slumped deep in rocking chair and she too snores slow and steady.

Stubby Pringle stands up. He takes dress and puts it under tree, fine dress, fancy dress, dress waiting now for small girl to wake and wear it with smiles and joy of living. He sets wooden horse beside it, fine horse, proud horse, snorting-into-distance horse, cat-hips crouched, waiting now for waist-high boy to wake and ride it around the world.

Quietly he piles wood on fire and banks ashes around to hold it for morning. Quietly he pulls on hat and wraps bandanna around and shrugs into skimpy-lined jacket. He looks at old rocking chair and tired woman slumped in it. He strides to outer door and out, leaving door open. He strides back, closing door with heel behind. He carries other burlap bag wrapped around box of candy, of fine chocolates, fancy chocolates with variegated interiors. Gently he lays this in lap of woman. Gently he takes big old shawl from wall nail and lays this over her. He stands by big old bed and looks down at snoring man. “Poor devil,” he says. “Ain’t fair to forget him.” He takes knife from pocket, fine knife, seven-bladed knife, and lays this on blanket on bed. He picks up gloves and blows out lantern and swift as sliding moon shadow he is gone.

High high up frosty clouds scuttle across face of moon. Wind whips through topmost tips of tall pines. What is it that hurtles like hurricane far down there on upslope of last low ridge, scattering drifts, smashing through brush, snorting defiance at distance? It is flop-eared ewe-necked cat-hipped roan, iron boned and dynamite fueled, ramming full gallop through the dark of night. Firm in saddle is Stubby Pringle, spurs ajingle, toes atingle, out on prowl, ready to howl, heading for the dance at the schoolhouse in the valley. He is ten feet fall, great as a grizzly, and the roan is gigantic, with wings, soaring upward in thirty-foot leaps. They top out and roan rears high, pawing stars out of sky, and drops down, cat-hips hunched for fresh leap out and down.

Hold it Stubby. Hold hard on reins. Do you see what is happening on out there in the valley?

Tiny lights that are schoolhouse windows are winking out. Tiny dark shapes moving about are horsemen riding off, are wagons pulling away.

Moon is dropping down the sky, haloed in frosty mist. Dark grey clouds dip and swoop around sweep of horizon. Cold winds weave rustling through ice-coated brushes and trees. What is that moving slow and lonesome up snow-covered mountainside? It is a flop-eared ewe-necked cat-hipped roan, just that, nothing more, small cowpony, worn and weary, taking its rider back to clammy bunk in cold line cabin. Slumped in saddle is Stubby Pringle, head down, shoulders sagged. He is just another of far-scattered poorly-paid patched-clothes cowhands who inhabit these parts. Just that. And something more. He is the biggest thing there is in the whole wide roster of the human race. He is a man who has given of himself, of what little he has and is, to bring smiles and joy of living to others along his way.

He jogs along, slump-sagged in saddle, thinking of none of this. He is thinking of dances undanced, of floorboard unstomped, of willing women left unwhirled.

He jogs along, half-asleep in saddle, and he is thinking now of bygone Christmas seasons and of a boy born to poverty and hard work and make-do poring in flicker of firelight over ragged old Christmas picturebook. And suddenly he hears something. The tinkle of sleigh bells.

Sleigh bells?

Yes. I am telling this straight. He and roan are weaving through thick-clumped brush. Winds are sighing high overhead and on up the mountainside and lower down here they are whipping mists and snow flurries all around him. He can see nothing in mystic moving dimness. But he can hear. The tinkle of sleigh bells, faint but clear, ghostly but unmistakable. And suddenly he sees something. Movement off to the left. Swift as wind, glimmers only through brush and mist and whirling snow, but unmistakable again. Antlered heads high, frosty breath streaming, bodies rushing swift and silent, floating in flash of movement past, seeming to leap in air alone needing no touch of ground beneath. Reindeer? Yes. Reindeer strong and silent and fleet out of some far frozen northland marked on no map. Reindeer swooping down and leaping past and rising again and away, strong and effortless and fleeting. And with them, hand on their heels, almost lost in swirling snow mist of their passing, vague and formless but there, something big and bulky with runners like sleigh and flash of white beard whipping in wind and crack of long whip snapping.

Startled roan has seen something too. It stands rigid, head up, staring left and forward. Stubby Pringle, body atingle, starts too. Out of dark of night ahead, mingled with moan of wind, comes a long-drawn chuckle, deep deep chuckle, jolly and cheery and full of smiles and joy of living. And with it long-drawn words.

We-e-e-l-l-l do-o-o-n-e . . . pa-a-a-artner!

Stubby Pringle shakes his head. He brushes an icicle from his nose. “An’ I didn’t have a single drink,” he says. “Only coffee an’ can’t count that. Reckon I’m getting soft in the head.” But he is cowman through and through, cowman through to the marrow. He can’t ride on without stopping to check anything strange on his range. He swings down and leads off to the left. He fumbles in jacket pocket and finds a match. Strikes it. Holds it cupped and bends down. There they are. Unmistakable. Reindeer tracks.

Stubby Pringle stretches up tall. Stubby Pringle swings into saddle. Roan needs no slap of spurs to unleash strength in upward surge, up up up steep mountainside. It knows. There in saddle once more is Stubby Pringle, moonstruck maverick of the Triple X, all-around hard-proved hard-honed cowhand, ten feet tall, needing horse gigantic, with wings, iron-boned and dynamite-fueled, to take him home to little line cabin and some few winks of sleep before another day’s hard work . . .

Stubby Pringle slips into cold clammy bunk. He wriggles vigorous to warm blanket under and blanket over.

“Was it worth all that riding?” comes voice of Old Jake Hanlon from other bunk on other wall.

“Why, sure,” says Stubby. “I had me a right good time.”

All right, now. Say anything you want. I know, you know, any dong-bonged ding-busted dang-blatted fool ought to know, that icicles breaking off branches can sound to drowsy ears something like sleigh bells. That blurry eyes half-asleep can see strange things. That deer and elk make tracks like those of reindeer. That wind sighing and soughing and moaning and maundering down mountains and through piny treetops can sound like someone shaping words. But we could talk and talk and it would mean nothing to Stubby Pringle.

Stubby is wiser than we are. He knows, he will always know, who it was, plump and jolly and belly-bouncing, that spoke to him that night out on wind-whipped winter-worn mountainside.

We-e-e-l-l-l do-o-o-n-e . . . pa-a-a-artner!

*****